On the surface, the foundations of job sequencing in considering the Weighted Shortest Job First (WSJF) prioritization schema seem logical. Do the smallest job with the greatest cost of delay first to deliver the greatest economic benefit. Though, in practice, it can be much more challenging. To survive and thrive in the post-digital economy, organizations need to change how they produce products, interact with customers, and define and prioritize work. To succeed in each of these areas requires a significant shift in organizational behavior, including how leaders interact with their peers.

But, how did we get here?

Why does what seems right feel so hard?

What can we do?

Siloed behavior and organizational politics

Organizational structure and a slow operating cadence have created a specific environment within workplaces. One where large organizations encourage people and leaders to prioritize the work system over customer needs and speed to market.

It’s not their fault; it’s the system they inherited.

In the decades following the Second World War, the capacity to serve consumer needs had been owned almost entirely by large organizations with the capital to establish complicated supply chains and manufacturing processes. These organizations, not the consumer, dictated products, delivery cadences, and market rhythms. Until recently, those behaviors proved profitable.

2001 proved to be a proverbial “canary in the coal mine,” which indicated business disruption on the horizon. With the mass adoption of the internet, software distribution was no longer reserved only for organizations with the capital and infrastructure to produce thousands of diskettes and manuals. The dot-com era brought forth an environment that allowed any developer with access to the internet the ability to distribute software without the overhead of production. If they intended to compete, large software companies realized that they needed to be more customer-centric, faster, and value-focused. Thus, the drafting of The Agile Manifesto.

In 2021, accelerated by COVID, nearly all businesses across every sector are facing the same awakening that software companies did in 2001—no industry is safe from disruption. This time around, we’ve witnessed minimal to zero barriers to entry, a global workforce that has thrived working from anywhere, supply chains that are more nimble than ever, and desktop manufacturing capabilities that are largely inexpensive.

If storied businesses aim to survive in the threat of total disruption, they must change organizational behaviors related to strategy, workflow, and systemic behavior. Though, to change these behaviors, it’s important to understand why organizations behave the way they do.

Win culture

Win culture is pervasive within the organizational system and is the greatest challenge to overcome. The culture of winning has been hardwired into many of us from a young age, was fueled throughout the educational experience, and is carried forward into our careers.

Starting in elementary school, students are tested and ranked based on their perceived abilities. These tests determine who is placed in gifted programs, remedial programs, or in a more traditional track. Parents desperate to see their children succeed and outperform their peers push them into after-school STEM programs, language studies, and other activities. Once on the advanced track, students compete to be among the best of their group. Only the best of the best will be admitted to the best colleges. Only the best from the best colleges will be accepted into the best graduate schools and offered the most prestigious jobs.

From there, the need to win is amplified in the workplace. As one climbs the corporate ladder, the opportunity for advancement shrinks and the need to win over one’s peers becomes more frantic. Winning sometimes surpasses the team, the customer, and even the organization. It becomes about beating the competition to achieve more power, prestige, and income.

Sound familiar? This is the system we have built. To paraphrase W. Edwards Deming, a system left unmanaged becomes inherently selfish, and only management can change the system. It begins with you and how you make decisions related to defining and prioritizing work.

Take an economic view

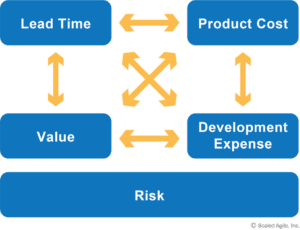

The first principle to embrace in defining and prioritizing work, as supported by the Scaled Agile Framework® (SAFe®), is to take an economic view.

In any organization, for-profit, nonprofit, and everything in between, economics must be the primary determinant of job sequencing. Or, which jobs can I do in the shortest amount of time that will generate the most revenue, save the most on expenses, or reduce our exposure to the greatest amount of risk?

Some may argue that the statement above may not seem very customer centric, but I would argue. Consider the perspective of a nonprofit, where the ultimate goal is to serve the most beneficiaries as possible while being a good steward of donor dollars. To be successful in this regard requires taking an economic view. Consider the perspective of a for-profit, and a quote from Sam Walton, founder of WalMart. “There is only one boss. The customer. And he can fire everybody in the company from the chairman on down simply by spending his money somewhere else.” If an organization is building products that don’t represent the greatest benefit to the customer when the customer desires the benefits, the customer won’t buy the products or services. To understand which products/services/features the market demands, we must take an economic view.

Apply systems thinking

With an economic perspective in mind, the next principle supported by SAFe is to apply systems thinking. Or, accept the very real possibility that the most important job for an organization to pursue may not be the job that you personally feel is most important. One of the biggest problems with organizations that embrace a hierarchy without the benefit of a secondary operating system is that it’s easy to become myopic. People become enamored with the success of their silo and often forget that their organization alone doesn’t deliver customer value.

Systems thinking encourages us to consider the whole value stream and customer journey. The principle also reminds us that the quality of a system (or customer experience) is only as good as its slowest/most painful component. As implied by Lean, to establish flow of any sort, we achieve the greatest benefit when we seek to optimize the slowest/weakest/most painful parts of the system. By applying systems thinking as part of an economic prioritization framework, we are reminded that the work we do is part of a system. The greatest benefit to that system may be investments in areas outside of one’s own area of direct influence.

WSJF

It’s hard to make decisions about the most appropriate prioritization of work. The difficulty is amplified when arriving at that prioritization requires consensus among peer groups that are typically in fierce competition with one another.

In my consulting career, I’ve seen many scenarios. Some where the people required to collaborate for prioritization struggled to even speak to one another. Some where people were reluctant to acknowledge that the task of another was more important than their own. As consultants and change agents who may be facilitating these prioritization discussions, we must lead with empathy. Project culture in organizations was often predicated with a “do this, or else” delivery requirement. At best, missed project delivery would kill a career. At worst, it could result in immediate termination. Many leaders and executives are in a position where their long-term bonuses are still tied to this sort of incentive, or have a hangover from management paradigms of the past. Overcoming these very real fears will require leading by example and providing psychological safety. Consider collaborating with an organization’s change partners to develop a strategy for helping decision-makers evolve with grace; pushing will not yield the desired result.

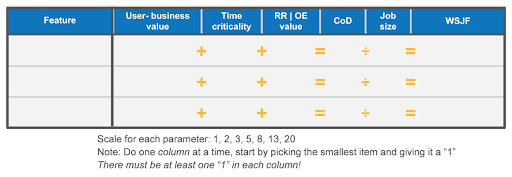

WSJF, the prioritization tool introduced by Reinertsen and applied by SAFe aims to make this difficult task easier. We consider WSJF in four micro-conversations:

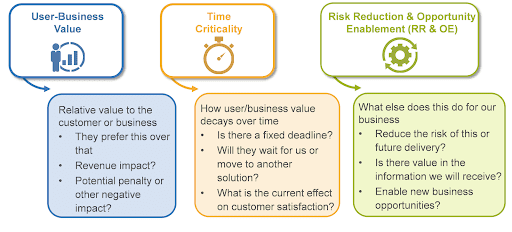

- Perceived user-business value

- Time criticality

- Risk reduction and/or opportunity enablement value

- Job size

The conversation is facilitated by reviewing each of these elements in isolation from the others. For example, if we have a list of ten jobs, we’ll first determine the user-business value score for each using a modified Fibonacci sequence (1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 20) and scoring guardrails. The guardrails should represent work that has been done previously to ensure consistent estimation. In my experience, I’ve found it helpful to have points of triangulation identified for each element of WSJF that represent a 2, 8, and 20.

WSJF is calculated by first determining the cost of delay through the summation of the user-business, time criticality, risk reduction and/or opportunity values, and then divided by job size. Based on the definition of the feature at the time, architects and other people who are responsible for delivering the work, will determine the job size independently of the other values.

Considering Reinertsen’s guidance, we agree that the jobs with the highest WSJF value represent the highest-value jobs that can be done in the shortest time possible.

It’s also worth noting that the WSJF prioritization isn’t final. We need to keep other factors top of mind, such as dependencies and availability of skills. And we need to make sure we always consider the economics and greatest benefit to the system.

Just-enough thinking helps us move faster

Consider the 10th principle behind the Agile Manifesto: the art of maximizing the amount of work not done is essential. We know that given the 80/20 rule, 80 percent of the value of a product comes from 20 percent of its features. The rest are rarely if ever, used.

Consider your bank’s website. I suspect that when you log into your account, you focus on three primary functions: reviewing your checking account, reviewing your savings account, and transferring money between the two. Not that loan applications, external transfers, and mobile deposits aren’t important. But to get the most value in the shortest amount of time possible, you likely focus on surfacing checking, savings, and transfer first. Additional functionality would come in a subsequent release. Waiting until all of the functionality was complete before launching the online banking platform likely seems foolish in the context.

WSJF forces us to focus on the features or ideas that are going to drive the most value at a given point in time. What are the checking, savings, and transfer functions relevant to you? Are you choosing to look at the work as a bank website, which is really big and would fail the prioritization conversation every time? Or have you broken the work up into smaller, high-value chunks? If you want your work to get prioritized, make sure that it’s small and highly valuable in the eyes of the customer. Small jobs move through the system (and delight customers) faster.

It requires leadership

Shifting our approach to prioritizing work is hard, but so is meaningful change. Winning in the post-digital economy depends on an organization’s ability to rapidly shift to meet changing market conditions and customer demands. Leaders who position themselves and their teams to be resilient in the face of change will win the digital future. Those who delay or don’t change will struggle to remain relevant.

What’s probably hardest of all is that for those in a leadership role, it’s highly unlikely that anyone will give them permission to behave in this way. In fact, doing so may come at great risk. Being a change agent is a difficult and thankless role, but one that organizations need now more than ever. If you’re a leader reading this post, it’s likely that your organization is already on the path to changing its work habits. It’s now up to you, the leaders, to determine how successful the change, and your organization’s future, will be.

About Adam Mattis

Adam Mattis is a SAFe Program Consultant Trainer (SPCT) at Scaled Agile with many years of experience overseeing SAFe implementations across a wide range of industries. He’s also an experienced transformation architect, engaging speaker, energetic trainer, and a regular contributor to the broader Lean-Agile and educational communities. Learn more about Adam at adammattis.com.

Share:

Back to: All Blog Posts

Next: Planning to 100% Capacity? Don’t Do It!