This post is the second in a series about success patterns for large solutions. Read the first post here.

Backlog refinement is integral to the Scrum process because it prevents surprises and maintains flow in iterative development. Regular backlog review ensures the backlog is ready for iteration planning. An Agile team understands how much they still need to refine the backlog items before the next iteration planning and beyond.

When applying SAFe® to large, complex, cyber-physical systems, you must expand backlog refinement to include more viewpoints. The complexity of a large solution is rarely fully comprehended by one or a few individuals, and the size of the large solution exacerbates the impact of risks that can escape into large solution planning.

So how do we find the balance between overpreparation, which limits ownership and innovation by the solution builders, and under-refinement, which can undermine the solution and the flow of value delivery?

To answer these questions, we adapted the following success patterns for large solution backlog refinement.

Use the Dispatcher Clause

The dispatcher principle guides large solution refinement by preventing the premature dispatch of requirements to Agile Release Trains (ARTs), solution areas, or Agile teams. Premature dispatching can cause risks like:

• Misalignment in the development of different solution components

• Missed opportunities for economies of scale across organizational constructs

• Sub-optimization of lower priority solution features

In contrast, making the right trade-off decisions at the right level drives holistic and innovative solutions.

Key stakeholder viewpoints that are often overlooked include marketing, compliance, customer support, and finance. Ensuring these voices are heard during refinement work can prevent issues that might remain undetected until late in the solution roadmap.

For complex solutions, we discovered that a planning conference is more effective than pre-and post-PI Planning events alone. This event mimics a PI Planning event and is intended to align upcoming PI work across ARTs and solution areas. To keep the conference focused and productive, it should only include representatives from the participating ARTs. We will cover specific planning conference details in a later blog post.

The goal of the planning conference is to provide a boundary for the large solution refinement work. Preparation for key decisions that can be made in the planning conference should be part of the refinement work. But making key decisions is part of the planning conference. However, key stakeholder inputs that cannot be reasonably gathered during the planning conference should be included in the refinement work.

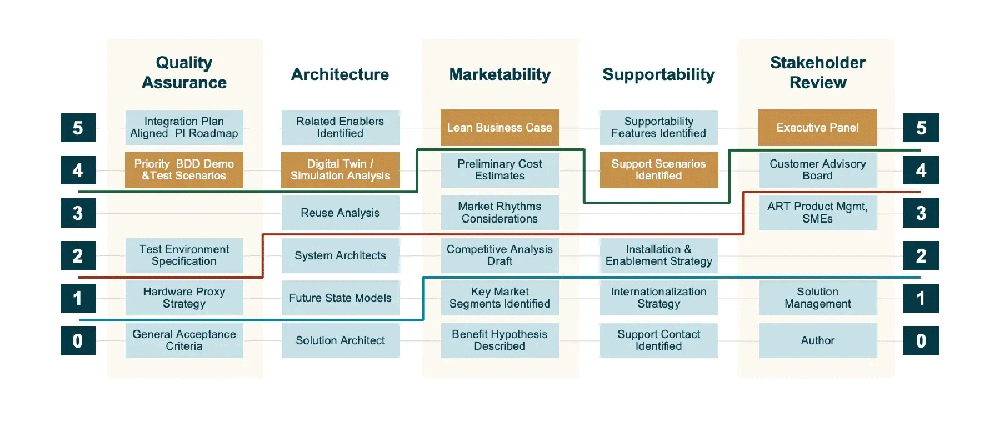

For example, in Figure one, a review of the key behavior-driven development (BDD) demo and testing scenarios by a customer advisory board is valuable input in refinement. The customer advisory board will not attend the two-day planning conference, so their advance input provides guardrails on the backlog work that’s considered.

Agree on the Definition of Ready

The definition of the readiness (DoR) criteria for a large solution backlog is often multidimensional. Consider, for example, the architectural dimension of the solution. The architecture defines the high-level solution components and how they interact to provide value. The choice of components is relevant to system architects in the contributing ARTs and stakeholders in at least these areas:

• User experience

• Compliance

• Internal audit and standards

• Corporate reuse

• Finance

Advancing the backlog item—a Capability or an Epic—through the stages of readiness often requires review and refinement from the various stakeholders.

Figure one is an example Definition of Ready Maturity Model. It shows the solution dimensions that must be refined in preparation for the solution backlog. Levels zero to five show how readiness can advance within each dimension. The horizontal contour lines show that progression to the intermediate stages of readiness is often a combination of different levels in each dimension.

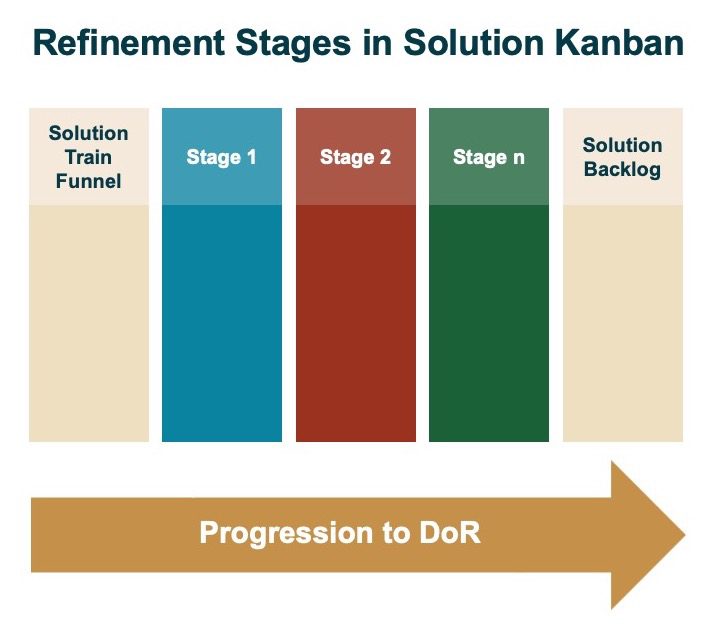

This delineation is helpful when monitoring the progression of a backlog item to intermediate readiness stages on a Kanban board.

The key to balancing over-preparation and under-refinement is to distinguish between work that an ART or solution area can complete independently without a high risk of rework. For example, final costs could be prohibitively high without a Lean business case to scope the solution. Another common high-risk impact of under-refinement is unacceptable usability caused by the siloed implementation of Features by the ARTs.

The Priority BDD and Test Scenarios in Figure one represent how features are used harmoniously. These scenarios provide guardrails to help ARTs prioritize and demonstrate parts of the overall solution without significant rework of a PI.

Identifying the dimensions, levels, and progression of readiness is a powerful organizational skill for building a large solution.

Leverage Refinement Crews

Regular large solution refinement is necessary to ensure readiness. The complexity of a large solution warrants greater effort and participation than Solution Management can cover. And the number of key decisions grows in direct proportion to the size of a solution.

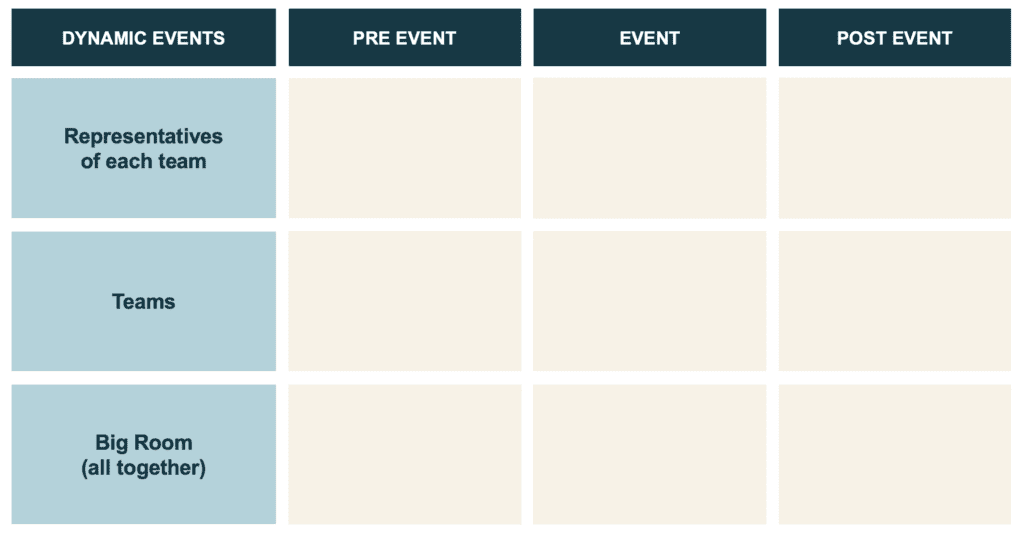

Our experience shows that roughly 10 percent of those who participate in large solution development should participate in a regular refinement cadence. If the total participation is 450 people, then 45 representatives from across ARTs or solution areas should set aside time for weekly refinement iterations.

Backlog refinement for a large solution requires more capacity than a typical backlog refinement session. The refinement crews determine a cadence of planning, executing, and demonstrating the refinement work. One-week iterations, for example, help drive focus on refinement to ensure readiness.

We also discovered that refinement crews of six to eight people should swarm refinement work within iterations. These groups are usually created based on individual skills and their representation within stakeholder groups. Alignment with crews and dimensions or skillsets is determined during the planning of refinement iterations. The goal is always to move the funnel item to the next refinement maturity level in the next iteration.

Our experience says that each refinement crew requires at least three to four core participants. The other crew members can come from stakeholder organizations outside the Solution Train.

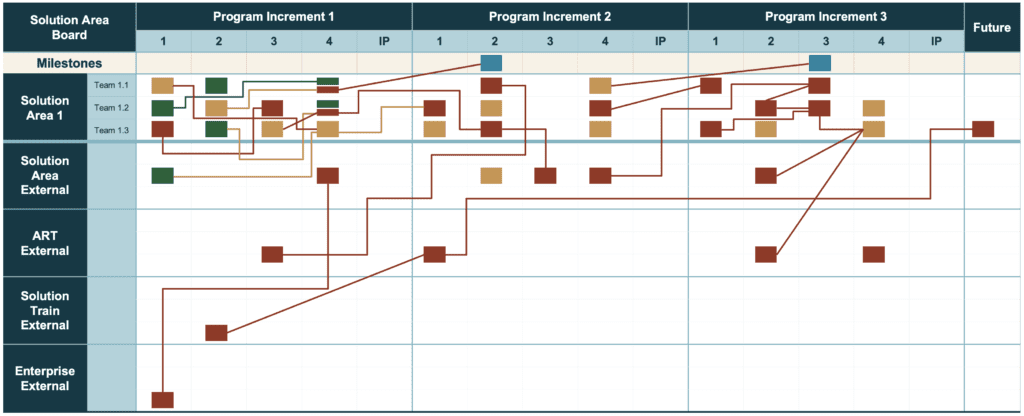

Readiness progress must be reviewed on a regular cadence with solution train progress. Progress can be represented in the Solution Kanban between the Funnel and Backlog stages, as shown in Figure two. In our example, these stages replace the Analyzing state provided as a starting point in SAFe.

The organization must also allow each refinement step to vary over time, as it makes sense for the solution. For example, as the development of the solution progresses toward a releasable version, the architecture should stabilize. Therefore the readiness of the backlog item in the architecture dimension should progress very quickly, if not skip some readiness steps. As solutions approach a major release, the contributors’ capacity can shift from readiness to execution of the current release or readiness for the next release.

Because refinement happens in a regular cadence of iterations, weekly, for example, the refinement crews should be empowered to make these decisions in refinement iteration planning.

Employ Dynamic Agility

So is there a definitive template of dimensions with levels and a step-by-step process for determining the DoR? Not quite. And we don’t think that a prescriptive process is best for most organizations.

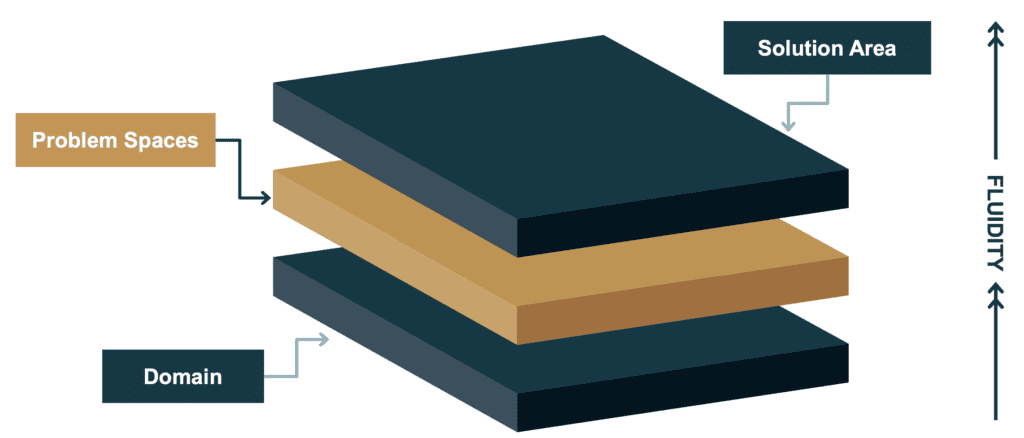

Instead, we advocate for using the organizational skill of dynamic agility.

As the size and complexity of a solution grow, so do the number and type of variables: compliance type, hardware types, skills required, size of the development organization, size of the enterprise/business, specialization of customer types, and so on. This complexity is augmented by company culture challenges, workforce turnover, and technology advancements in emerging industries.

Individuals’ motivation and innovation suffer when they get lost in the morass of complexity. When things don’t get done, more employees are added to help fix the problem. This workforce growth only magnifies the complexity again.

In contrast, the organizational skill of dynamic agility stimulates autonomy, mastery, and purpose for individuals within teams, teams-of-teams, and large solutions.

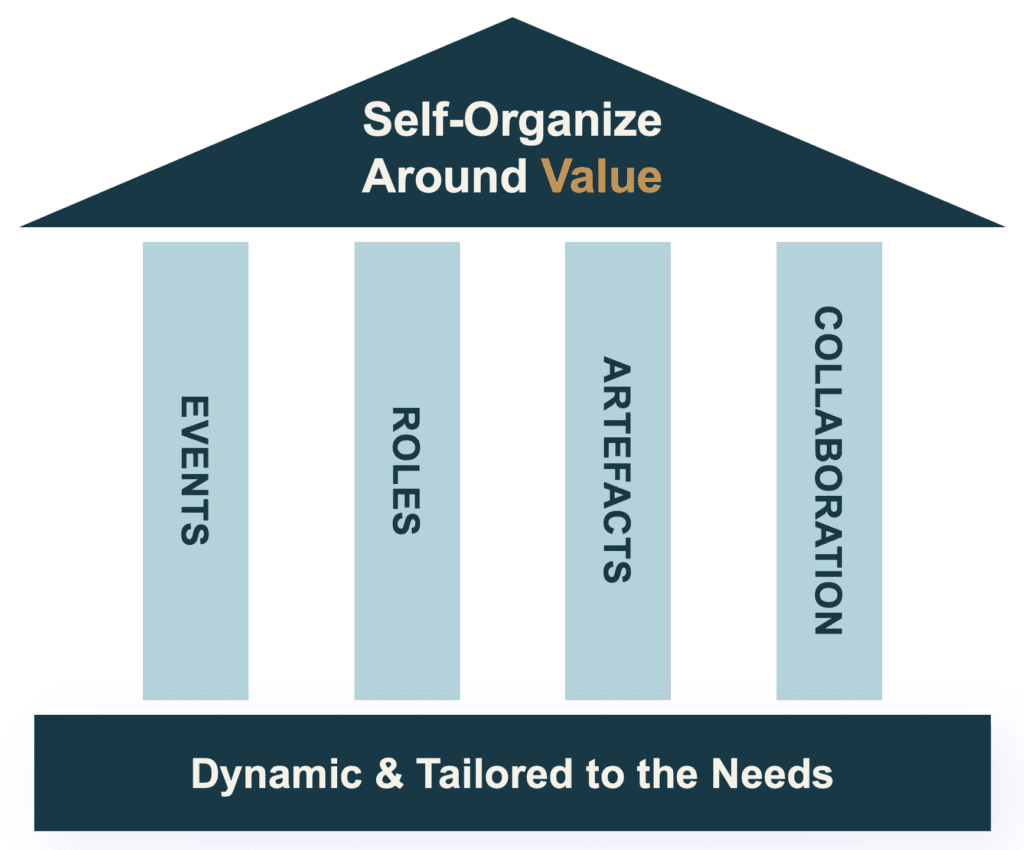

Consider the House of Dynamic Agility represented in Figure three.

How can dynamic agility be applied to large solution refinement? DoR identification and maintenance of its dimensions and levels happen through a regular cadence of the right events. How often should these occur, for how long, and who should attend? What elements will represent and communicate the DoR? What roles are best suited to own and facilitate the management and use of DoR over time? How will collaboration across the organization happen most efficiently for maximum benefit? These questions are best determined in the context of the large solution.

Conclusion

Large solutions require a balance of preparation and execution to achieve an optimal flow of value. Conducting backlog refinement in preparation for a large solution planning conference and PI Planning lets decomposed work items be implemented without risk of rework. Avoiding over-specification in refinement allows ARTs to innovate and accomplish within the guardrails of refinement. Enabling large solutions to leverage dynamic agility builds ownership, collaboration, and efficiency in a large-scale endeavor.

Look for the next post in our series, coming soon.

About Cindy VanEpps, Project & Team, Inc.

From crafting space shuttle flight design and mission control software at Johnson Space Center to roles including software developer, technical lead, development manager, consultant, and solution developer, Cindy has an extensive repertoire of skills and experience. As a SAFe® Program Consultant Trainer (SPCT) and Model-based Systems Engineering (MBSE) expert, her thought leadership, teaching, and consulting rely on pragmatism in the application of Agile practices.

About Wolfgang Brandhuber, Project & Team, Inc.

Dr. Wolfgang Brandhuber has been a Scrum Developer, Product Owner, Scrum Master, Chief Scrum Master, and Agile Head Coach in various Agile environments. His passion is large solutions. Since the advent of the large solution level in the Scaled Agile Framework in 2016, he has set up and helped solution trains improve their complex systems. During his 18 years as a professional consultant, he worked over 16 of those in the Agile world and more than nine years with SAFe. Among other certifications, he is a certified SAFe® Program Consultant Trainer (SPCT), a Kanban University Trainer (AKT), and an Agility Health Trainer (AHT).

About Malte Kumlehn, Project & Team, Inc.

Malte helps deliver complex ecosystems, people, Cloud, AI, and data-powered digital transformations toward business agility. He pioneers intelligent operating models for portfolios with large solutions as a SAFe® Fellow, advisory board member, and executive advisor in this field. He guides executives in developing the most challenging competencies that allow them to deliver breakthrough results through Lean-Agile at scale. His experience has been published by Accenture, Gartner, and the Swiss Association for Quality over the last ten years.

Learn more about Project & Team.