This is the second post in my short series on landing change well. Read the first post here.

Managing change is as much of an art as it is a science.

As we have learned through decades of project management and big-bang releases, even the best-planned and best-executed changes at large scale can land poorly.

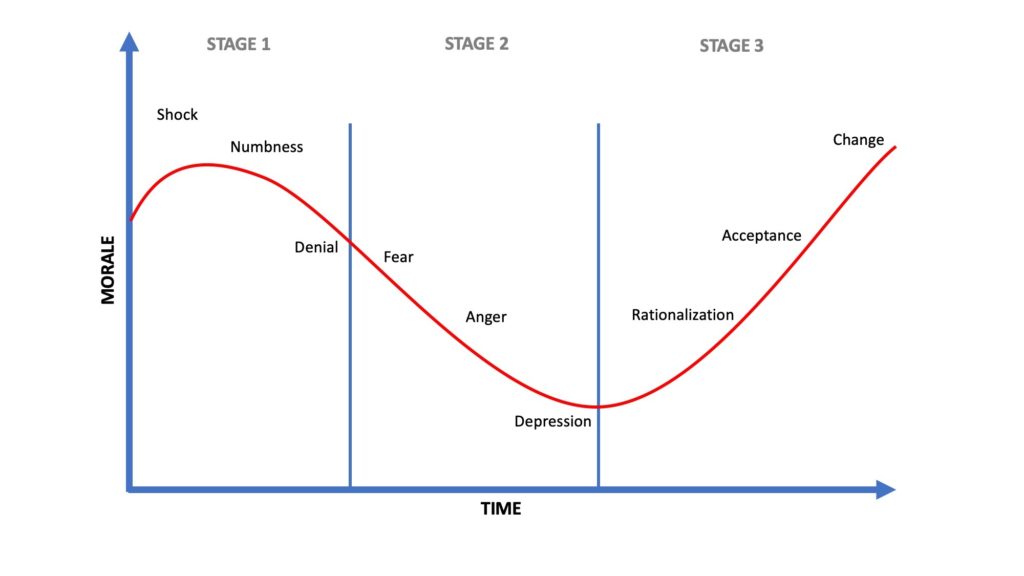

Consider a large software system change that impacts many disciplines within an organization. The change impacts the HR generalist, who has been doing her job effectively in the legacy system for years. Nobody asked her opinion of the new system and now that the new platform has arrived, she feels confused and inefficient. The same story is playing out with the sales team, finance, legal, product, and others. Big batches of change do not land well, because as people, we don’t handle change well.

Change is not typically something that we choose; it’s more likely something that is imposed upon us. Change is hard. Change is uncomfortable. Without the perspective of the why, change is outright painful.

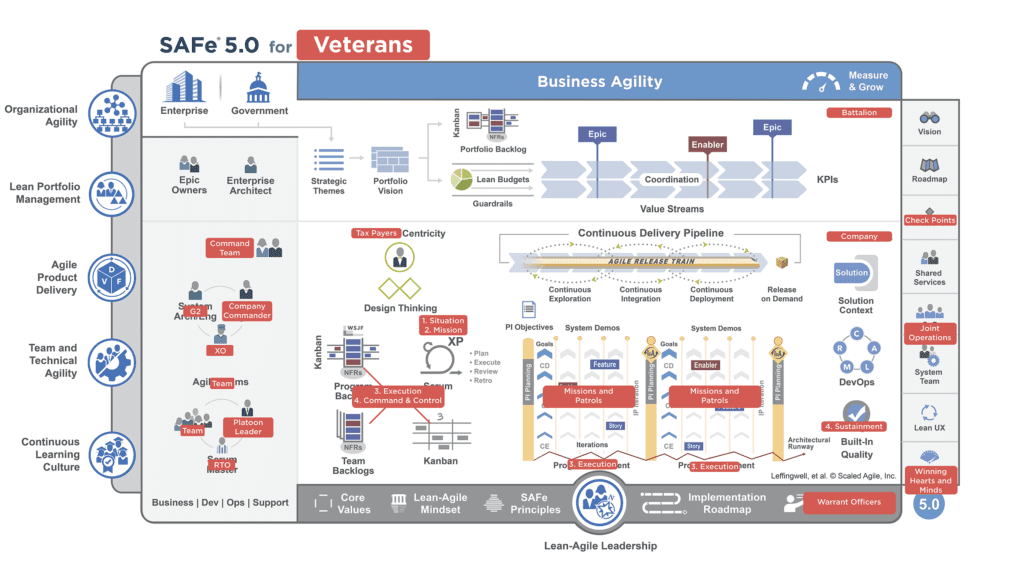

Several years ago while working with a client to adopt new ways of working, I was introduced to the discipline of change management (CM), and since, it has proven to be one of the most effective tools I’ve found to help organizations adopt a Lean-Agile mindset, strategy models, budgeting, and to deliver value.

The CM team helped me better understand the organization, determine who were my advocates and adversaries, as well as develop plans for how to best influence the organization. And, as was introduced to me by Lisa Rocha, how to avoid change saturation through the use of Change Air Traffic Control to ‘land change well.’

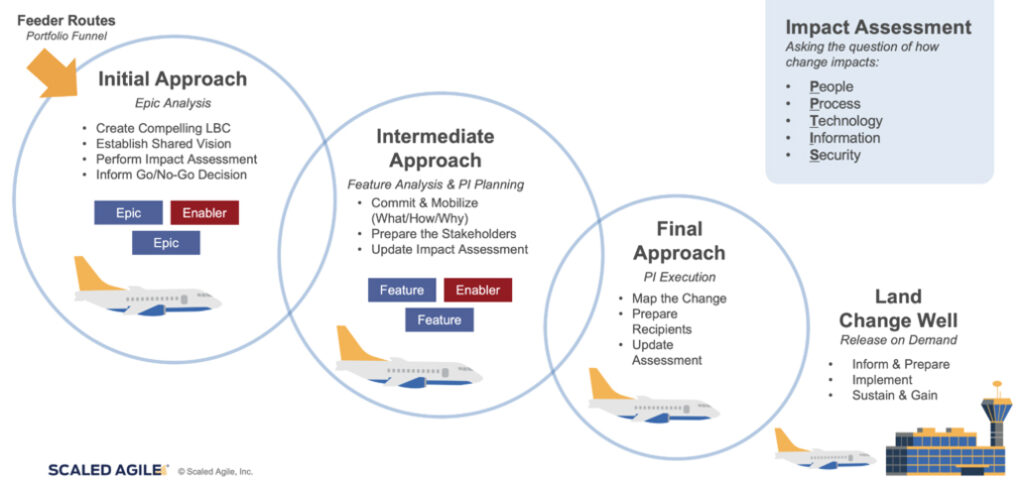

One of my favorite things about living in Denver is the drive to the airport. If you are familiar with the city, you know that the airport was built far outside of downtown on the plains (and when you landed in Denver for the first time, I’m sure your thoughts were similar to mine: where are the mountains?!).

What makes the drive from the city to the airport so interesting is that the lack of terrain combined with the Colorado blue sky makes it easy to see the air traffic patterns. This is a hugely effective metaphor for Lisa’s concept of Change Air Traffic Control: though you may have many changes in flight, you can only land one at a time.

After thinking deeper about Lisa’s idea, I started to realize that the phases of landing change with SAFe actually match air-traffic patterns rather well.

Phase 1: Feeder routes

Portfolio funnel

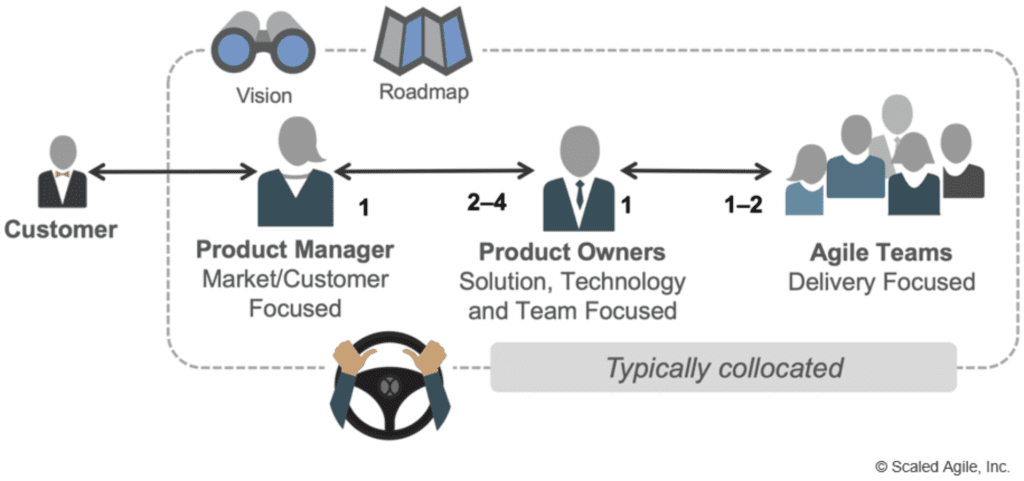

Change begins with an idea. In a Portfolio, these ideas are welcomed by everyone and are captured in the Portfolio funnel, which serves as an initial filter for ideas. Portfolio leadership explores each one and decides if the good idea aligns with the Portfolio strategy, if they want to learn more, or if the Portfolio is not ready to explore the concept at that time.

Phase 2: Initial approach

Epic analysis

When the Lean Portfolio Management (LPM) team identifies ideas that they are interested in exploring, they conduct an initial analysis to determine the feasibility, Value Stream impact, and other implications through the use of a Lean Business Case.

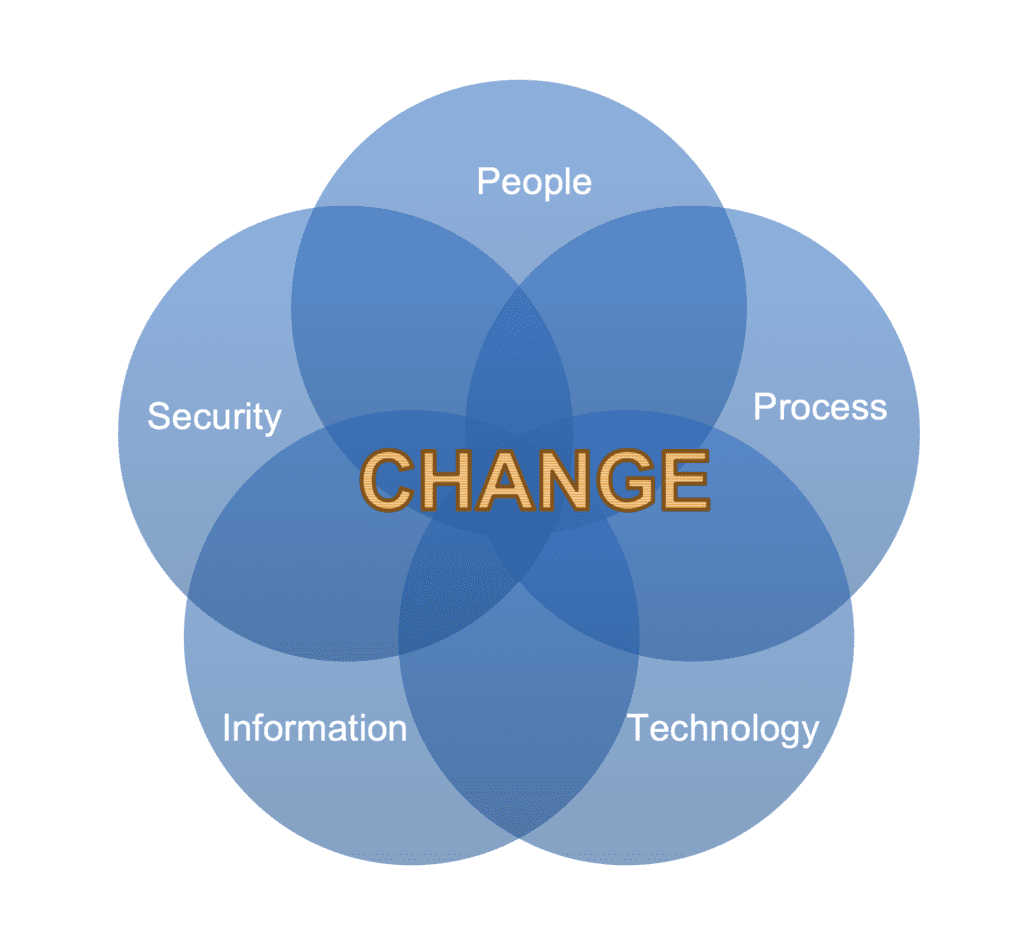

This is also the point where the change management team should be engaged to help answer questions around how the change will impact PPTIS, defined as:

People: Who are the people impacted by this change?

Process: What processes are impacted by this change?

Technology: What technology is impacted by this change?

Information: What data is impacted by this change?

Security: How is physical, informational, or personal security impacted by this change?

With the quick picture of the change becoming clear, the LPM team will make a decision whether it’s interested in experimenting further with the idea or not.

For the ideas earmarked for further experimentation, change managers will begin working with the LPM team to articulate the Vision (the reason why) for the change. As John Kotter often reminds us, people underestimate the power of vision by a factor of 10.

Phase 3: Intermediate approach

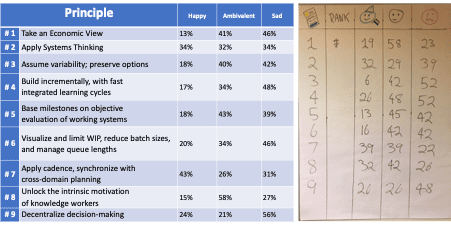

Feature analysis and PI Planning

Once the LPM team has prioritized an idea for investment (considering the Lean Startup Cycle), an MVP of the idea will be defined for the purpose of validating or invalidating the idea within the Continuous Exploration cadence of an Agile Release Train. Working with Product Management and the architecture community, change professionals will start articulating the what, the how, and the why of the change to begin preparing stakeholders who will be impacted. The change impact assessment is updated as a living artifact.

With guardrails for the work and change established, the solution teams are now ready to build the change. The handoff between strategy and solution happens at PI Planning.

Phase 4: Final approach

PI execution

The final approach for introducing change takes place during PI execution. While the Agile Teams are developing the solution representing change, change professionals continue their work by mapping the change to identify who is impacted, the best method to interact with each impacted party, and to determine how each group prefers to receive change.

This work, performed with the release function, helps prepare the organization and its customers for the release-on-demand trigger for value delivery.

Phase 5: Land change well

Release on Demand

Once the organization, the customers, or the market determine that the time is right to introduce change, all of the work done by the Portfolio, Agile Release Train, and change professionals will be put into action.

Though each has done their best to prepare the receiving entity for change, there is more to landing change well than simply preparing. We must also avoid change saturation, which is where the Air Traffic Radar comes in.

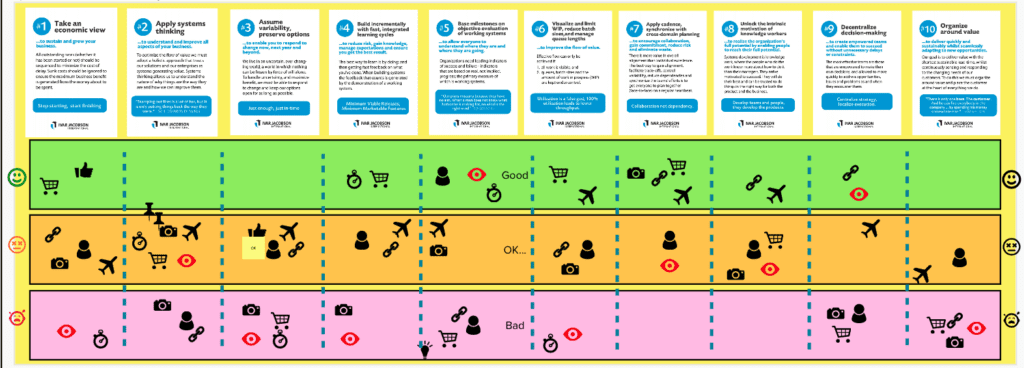

Monitoring Change with the Air-traffic Radar

It’s hard to prepare for what you cannot see, and most change falls into that category. To help avoid inundating our organization and our customers with too much change, we need to develop a mechanism to visualize the change that will impact a given audience.The best way I’ve found to describe these learning networks is to share the questions people in these networks are curious about. So, here’s my synthesis of a lot of research around how we share what we learn across enterprises.

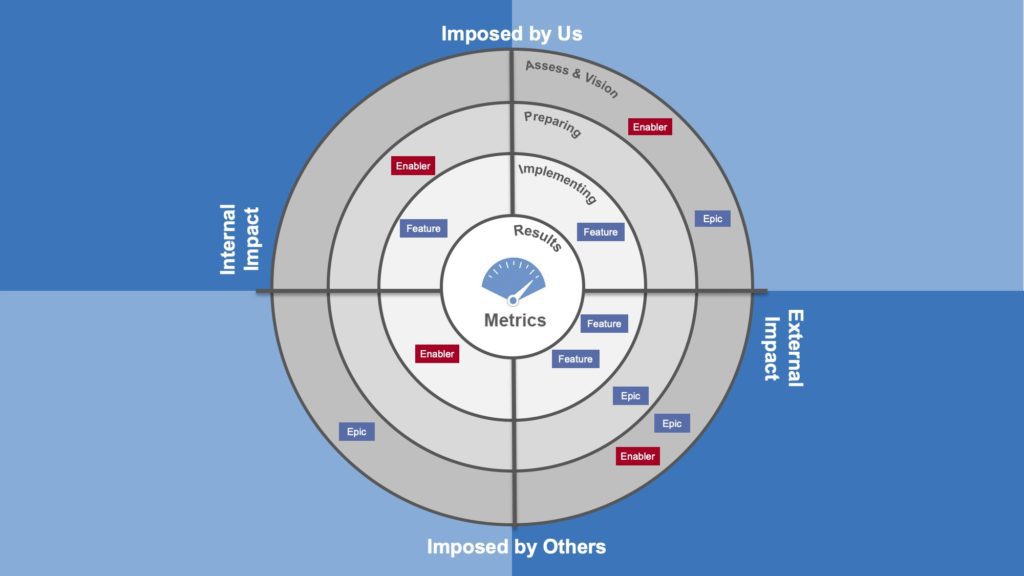

The concept of a change radar involves four perspectives: changes we are inflicting, changes being inflicted by others, changes impacting our internal customers, and changes impacting our external customers.

To better understand what changes are impacting us, we want to think back to the visual of the air-traffic pattern at the Denver airport: what changes are coming our way and at which horizon.

With the visual, we can start informing Portfolio and Program prioritization considering our customer’s appetite for change. As is often said: timing is everything. If we land the right change at the wrong time, we run the risk of losing strategic opportunities.

Change is hard! But with our change partners working with the Portfolio and Agile Release Trains, we can help our organizations achieve Business Agility, deliver value, and land change well.

About Adam Mattis

Adam Mattis is a SAFe Program Consultant Trainer (SPCT) at Scaled Agile with many years of experience overseeing SAFe implementations across a wide range of industries. He’s also an experienced transformation architect, engaging speaker, energetic trainer, and a regular contributor to the broader Lean-Agile and educational communities. Learn more about Adam at adammattis.com.

Share:

Back to: All Blog Posts

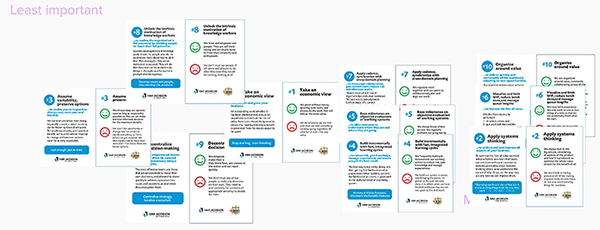

Next: Experiences Using the IJI Principle Cards