Who writes user stories?

Based on the Product Owner (PO) Framework article, POs manage and prioritize the team backlog.

However, this doesn’t directly answer who writes user stories. Does managing and prioritizing include writing stories? Should POs write most or all of the stories? Or should the Agile Teams?

This question arose when a new PO asked me for ideas for her team. She asked me, “Who writes the stories on your team?”

Although I gave the new PO an answer about my team, how we worked, and shared who touches stories, this basic question stayed with me.

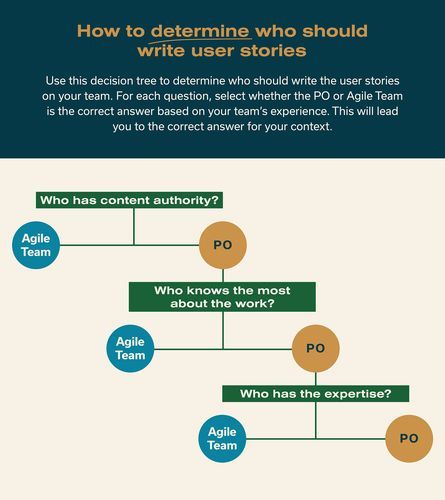

Who should write the user stories?

Here are three potential answers to consider:

- Agile teams should write the user stories

- POs should write the user stories

- It depends on the situation

I’ll explain my reasoning and how I reached for SAFe® guidance considering each possible answer. I also hope you’ll check out the user story-writing resources at the end of this post.

When Agile teams should write the user stories

Lean-Agile leaders have acknowledged a game-changing truth: attempting to ‘manage’ knowledge workers with traditional task management is counterproductive. Management visionary Peter Drucker was one of the first to point this out: “That [knowledge workers] know more about their job than anybody else in the organization is part of the definition of knowledge workers.

—SAFe Principle #8 article

To help answer the question of who writes user stories, I turned first to SAFe Principle #8, Unlock the intrinsic motivation of knowledge workers.

The importance of unlocking the intrinsic motivation of knowledge workers was never more apparent to me than when I became a PO. Many of my teammates had more experience with their expertise area and working on our courses than I did.

This applies across many fields, products, and enterprises: your teammates become experts in what they are doing because most of us want to succeed at work. Thinking about how to help your team individually and collectively find motivation is key, and recognizing team members’ expertise is a crucial way to build trust and respect to lead the work effectively.

The language in Principle #8 reminds me to define my role and sphere of influence. As a PO, I don’t manage people. However, for my team to produce great learning content, I must care about their knowledge, ideas, experiences, and expertise at each juncture of planning, refining, and iterating on the work they’re doing.

On my team, Agile teammates usually write user stories. Every teammate has expertise that I don’t have. It would be foolish of me as a PO to write every story when someone else on my team understands the details about accomplishing the work more than I do.

If I tried to represent their work by defining and writing every story, it could lead to too much rewriting. Rewriting a story is fine as we refine and understand more details and can often be done as a team activity alongside Backlog Refinement, estimation, and even Iteration Planning and it can be streamlined when the right expertise is applied as the story is discussed.

If I wrote every story, I’d probably have to consult on and rewrite plenty (most) of them. Worse, it could demotivate my teammates if every story was dictated by their PO.

That said, what I do as my team refines stories is:

1. Provide a strong voice in crafting acceptance criteria

2. Remind the team of our definition of done for work

3. Share who the customer is, and what they want

4. Work with the team (collectively and individually) on what counts as a “minimum viable story” for our backlog.

You’ll find an example of a minimum viable story at the end of this post.

Why POs should manage, but not always write, user stories

While any team member can write stories at any time, it is the PO’s responsibility to ensure that they are well-formed and aligned with product strategy. The PO clarifies story details, applies user-story voice, ensures ‘INVEST’ characteristics are present, assists with story splitting, defines enablers, and incorporates behavior-driven design (BDD) to ensure stories support continuous value flow. The PO also allows space for ‘local’ stories and spikes that advance product design but are not derived explicitly from ART-level features.

—Product Owner article

My second answer to who writes user stories comes from the PO Framework article.

POs “manage” the team’s backlog and have content authority. This can mistakenly turn into an expectation that POs write the stories.

POs may write all the stories if:

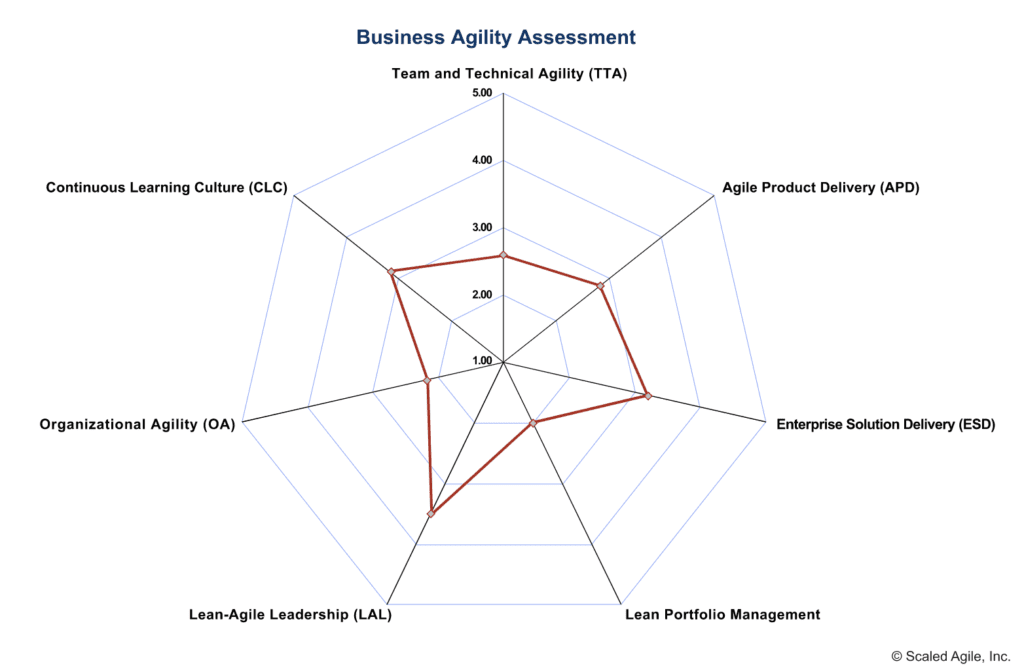

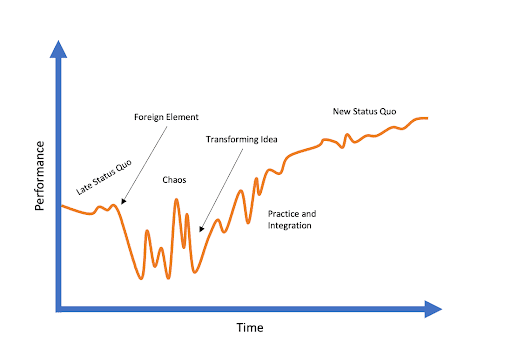

1. Agile teams are not yet feeling the benefits of transformation. Therefore, they may be slow to embrace the work of writing stories themselves. It can become “another thing to do” or “taking time away from doing the actual work.”

2. They want to ensure the ART and team backlogs are aligned, and stories in the team’s backlog meet the definition of done and support ART progress.

However, if the PO writes every story, they will have little time to perform all the functions POs are otherwise busy with!

For me, it’s important to note the Framework talks about management, not authorship. In fact, the PO article talks about guiding story creation rather than authoring stories.

We don’t find SAFe specifying that POs author the team backlog. What a PO does in order to manage the backlog and guide story creation is both different and deeper than simply writing everything in it:

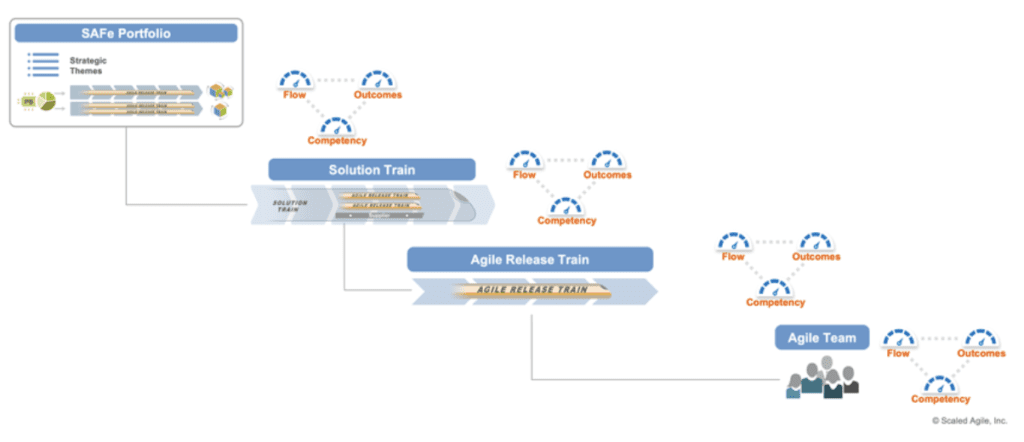

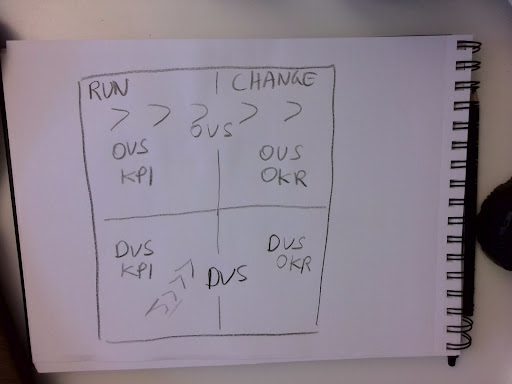

- Strategizing across the ART to meet ART-level objectives

- Working with Product Managers, Business Owners, and the RTE to deeply understand the matrix of metrics the ART is using, strategic themes, and how both are applied

- Working closely with Product Managers, who own the ART Backlog, to refine features

- Working closely with the team and stakeholders to decompose features into stories

- Ensuring stories meet user needs and satisfy the team’s definition of done

- Being the go-to person to share decisions the team is making on “how” to complete the work and how it may show up in meeting objectives

- Prioritizing which work to do when so the team can accomplish its goals and contribute to the ART goals while maintaining flow

Here is the guidance I shared with another PO on the idea of the PO writing every story.

Becoming a story-writing PO will:

- Create demonstrable work for the PO

- Codify the (damaging) idea that writing stories is a bureaucratic task

- Lead to future disagreements or dissatisfaction about what should be included in the scope of this work

- Set POs up to be the target for those disagreements and dissatisfactions

Here’s what it won’t do.

It won’t remove the need for teams to plan their work together to achieve flow or avoid rework or misunderstandings about what value is being delivered or how the team is delivering it.

For these reasons, I refuse to become a story-writing PO. I insist my team come together to discuss work and decide who is best informed to write a story. I further drive us to consider all of our stories in refinement so there are multiple teammate eyes on it.

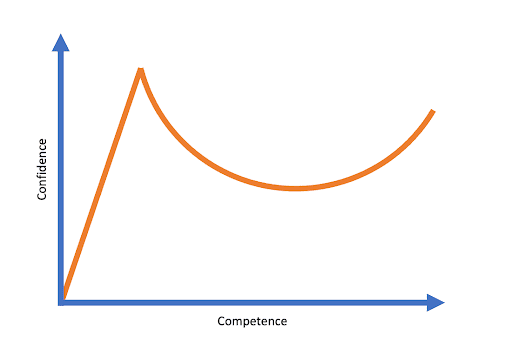

The immediate result of this process with some of my teammates early on was frustration: “I’m so busy that asking me to write about my work instead of doing it feels like you’re wasting my time.”

Over time, it has borne other, much more nourishing fruit for the team, including:

- More paired work and team stories

- Better flow and processes to manage flow

- Growth of T-shaped skills

- Improved understanding and thought about customer centricity across the team

- An understanding of each other’s areas of expertise and how work connects on a cross-functional team

If you have teammates who resist writing stories, I recommend you surface this conflict sooner than later and work through it upfront.

The most knowledgeable people write the user stories

I believe the best answer to who writes user stories is the answer to “Who knows the most about this work?”

Sometimes the answer may be the PO because they’ve gathered the most information.

In this case, it’s best for the PO to write the story.

- I have been in an org-wide or ART-level meeting and know about work for every team. This has included tooling updates, requests to prepare specific demos of our work for different kinds of audiences, work around specific milestones, or professional development requests.

- It is work that came out of my meetings with other teams to service dependencies.

- It is walk-up work coming from changes or needs that weren’t surfaced before.

- Talking with an internal or external customer helped me understand a need we had not previously written stories to meet.

It is rare I would write a story for work I am doing. In the above cases, the work would be handled by the team. By writing the story, I am capturing the need as I understand it but not carving the story in stone.

When thinking of how stories enter the backlog, I find it useful to remember the three Cs of story writing:

- Card

- Conversation

- Confirmation

The C for conversation is most relevant to my mindset on this. The story is a promise our team will discuss this need and decide how to deliver value on it.

The conversation could include:

- Refining our understanding of the user and their need

- Revising acceptance criteria

- Discussing who might start the work on it or how the team will deliver the work’s value

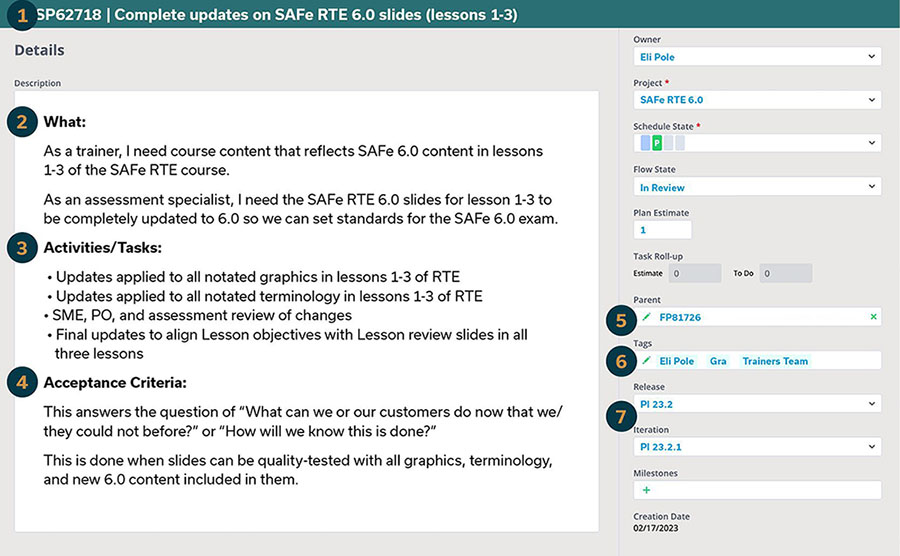

This is the minimum viable story criteria my team uses.

1. Story title: Provide a name that accurately describes the work

2. What: Give a description of the work

3. Activities or tasks: Break down what it will take to complete this work

4. Acceptance criteria: This answers the question, “What can we or our customers do now that we or they could not before?” or “How will we know this is done?”

5. Parent: Connect it to a feature where possible

6. Tags: We note if this is a team story (more than one person tagged) or an individual contributor’s work (a single person tagged)

7. PI and Iteration: When we expect to start and complete this work

I encourage you to use this template as a jumping-off point.

Look through your backlog and think about who is and could write user stories with the most thoughtful details.

Story-writing resources

Now that I’ve shared my answer to who writes user stories, here are some resources to help write them.

- Stories video playlist

- Creating Your PI Backlog Content blog

- Writing and Splitting Stories guide

- Story Splitting on an Agile Team template

- Facilitator’s Guide to SAFe – Backlog Refinement

- Determine the Team’s Definition of Done template

If you want to receive helpful content like this for your role, don’t forget to set your role in SAFe Studio. This allows us to bring the best content to your SAFe Studio homepage. Set your role in SAFe Studio today.

About Christie Veitch

As a writer and education nerd who loves processes, Christie seeks to move the needle on what learners can do and what educators and trainers will try with learners. She designs and delivers compelling content and training and builds communities of avid fans using these resources as a Scaled Agile, Inc. Product Owner. Connect with Christie on LinkedIn.